In recognition of this year’s International Women’s Day, this blog is the first to report new findings from the State of Inclusion of Women in Cybersecurity Benchmark, a joint research project between my company, Aleria, and Women in CyberSecurity (WiCyS), a nonprofit organization dedicated to the recruitment, retention and advancement of women in cybersecurity. Our findings reveal a stark disparity between the levels of inclusion of women and men.

Our goal with this ongoing project is to identify the factors that influence the low representation of women in cybersecurity, by measuring inclusion. Our results strongly suggest that the lack of women in cybersecurity (and in other technical fields) has much less to do with a pipeline problem, and much more to do with the way women are treated in the workplace.

In particular, we find that women in cybersecurity are much more likely than men to be disrespected, especially by their peers and direct managers. Other major problem areas that reveal particularly strong gender disparities include Career & Growth and Recognition.

Why and how we measure inclusion

For the past several years I have been suggesting that it is unwise to focus on diversity as the sole metric used to set DEI targets and to measure progress. In a 2019 blog, I described a new way to measure inclusion by quantifying the day-to-day workplace experiences that impact employees.

In a nutshell, inclusion is about what organizations do, and diversity is the outcome. Trying to “fix diversity” directly is a bit like hoping to make your house warmer in the winter by lighting a match under the thermostat: you won’t improve things, and you may burn the house down. Inclusion instead is the collection of all the things happening in an organization that impact each employee’s ability to perform at their peak.

But how do you measure inclusion? A key is to understand that inclusion itself is invisible, but that we can measure “exclusion.” In particular, we have developed a platform where individual participants can anonymously and confidentially share specific experiences in the workplace that have interfered with their ability to do their work, or that had a negative impact on their satisfaction. We also ask participants to categorize each experience in terms of the general aspect it impacts (work-life balance, respect, compensation, etc.), and what caused it (company policy, leadership, peers, etc.). The experience descriptions provide qualitative data, while the categorization is used to calculate an “exclusion score” that quantifies the (negative) impact of the workplace experiences.

The combination of qualitative data (the description of the experience) and quantitative data (participant demographics and the categorization of experiences) provides immediate guidance on the biggest opportunities to improve inclusion, as well as clarity on what exactly is happening—and thus what initiatives to take.The combination of qualitative data (the description of the experience) and quantitative data (participant demographics and the categorization of experiences) provides immediate guidance on the biggest opportunities to improve inclusion, as well as clarity on what exactly is happening—and thus what initiatives to take.

The State of Inclusion of Women in Cybersecurity

In early 2023, Aleria partnered with WiCyS to conduct an initial “State of Inclusion of Women in Cybersecurity” study, which collected inclusion data from about 300 women, all working in cybersecurity. An initial report identified some of the key areas with the greatest impact on women’s workplace experiences. Among other things, we found that women’s experiences of exclusion stemmed mostly from their leadership, direct manager and peers. We found that women hit a “glass ceiling” about 6 years into their careers. And we found that the two areas causing most issues were lack of respect, and poor opportunities for career advancement.

In addition to its individual members, WiCyS works closely with more than 60 strategic partner firms, including leading organizations in cybersecurity as well as global leaders with significant cybersecurity teams (e.g., Amazon Web Services, Bloomberg, Ford, Google, Intel, JPMorgan, Meta, McKesson and Microsoft), as well as several universities and some government agencies. Leveraging this network, in late 2023 we expanded our initial study to collect data from all employees (not just women) across many of these and other cybersecurity organizations.

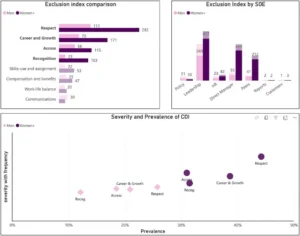

We have just completed our initial analysis of this industry-wide benchmark, and found some stunning results that underscore the gender disparities that exist in this space. The figure at the top of this blog is a screenshot from our interactive data visualization dashboard. Here are some of the key findings.

First, as we had found in our original study, the four “categories” with the highest exclusion scores, for both men and women, are Respect, Career & Growth, Access & Participation, and Recognition. What stands out with the new study is the gender disparity across these categories:

· For Respect, the exclusion score for women is 282, which is 2.5 times higher than the exclusion score for men (111).

· For Career & Growth, it’s a factor of 2.4 (171 for women vs. 70 for men)

· For Access & Participation, it’s a factor of 2.1 (115 for women vs. 56 for men)

· For Recognition, it’s a factor of 4.5 (103 for women vs. 23 for men)

When we look at the sources of experiences to understand who or what causes these stunning discrepancies, we found that, although Leadership is the highest source for both men and women, the impact is not that different across genders. However, there are huge gender disparities for the Direct Manager and Peers sources:

· The women’s score for Direct Manager, at 349, is 4.6 times higher than it is for men (76)

· The women’s score for Peers, at 248, is 5.1 times higher than it is for men (49).

These are staggering differences that speak to the daily abuses that women are subjected to during their day-to-day work.

To add some substance to these numbers, and to give readers an idea of the kind of situations that women have to deal with, here are just a few of the thousands of specific experiences that we have collected (note that by default we never share experiences unless the user has explicitly given us permission to do so, and we make sure that the content cannot be traced to the author):

· “When taking a call about a technical support issue, the male who called in upon hearing my voice said ‘I’d actually like to speak to someone technical who can help with this.’ ”

· “I am a software engineer was being assigned business analyst style work only. I told my engineering manager I wanted to do engineering work and not administrative work. My manager then went to my department and complained that I was not being a team player and was too ‘emotional’ in the workplace.”

· “I work in an environment that is at least 80% male. Some of my male colleagues curse too much, belch, and joke about inappropriate things for an office.”

· “Male peers would have important work conversations at lunch when I am not with them.”

· “I don’t feel comfortable wearing the clothing I feel my best in, because when I do, men in my department stare at my body.”

· “A male manager took me to a strip club and then kissed me.”

These are just the tip of the iceberg—and they are not the most disturbing experiences we have seen, because most of the really horrible ones are marked as “not shareable.”

Is it any wonder that women have been so reluctant to be forced to go back to the office every day? Male leaders who have been so vocal about return-to-office mandates should look at these stories and either be more accommodating, or should make it a top priority to clean up their act.

Where do we go from here?

It is unfortunate to mark International Women’s Day with yet another dataset painting such a bleak picture. However, unlike diversity data, which captures the lack of women but doesn’t explain why, the data we are collecting makes it abundantly clear what is happening.

In the words of WiCyS Executive Director Lynn Dohm, “In a world that continues to talk about diversifying the cybersecurity workforce, it was time to peel back the layers and look at the underlying issue… inclusion (or the lack thereof). By collaborating on this project to provide inclusion data, we’re now able to have more productive conversations with leaders and help drive the change that’s needed.”

Thanks to organizations like WiCyS that have the foresight to conduct these studies—and the capacity to create programming and other initiatives in support of women in the field—we are optimistic that in future years we will see an increase in the inclusion of women, not only in Cybersecurity, but in every other part of our society.